10,000 slides. And suddenly it’s about more than just technology.

Some numbers seem abstract. 10,000 slides is one such number. Until you open the first magazine. Until you hold the first slide up to the light. And realize that this isn’t a project you can put off “until sometime in the future.”

These are my parents’ slides. Their view of the world. Their lives captured on film. And as I sort through them, it becomes clear: if I don’t do this right now, these images will disappear at some point. Quietly. Without drama. Just gone.

These photos cannot be recreated

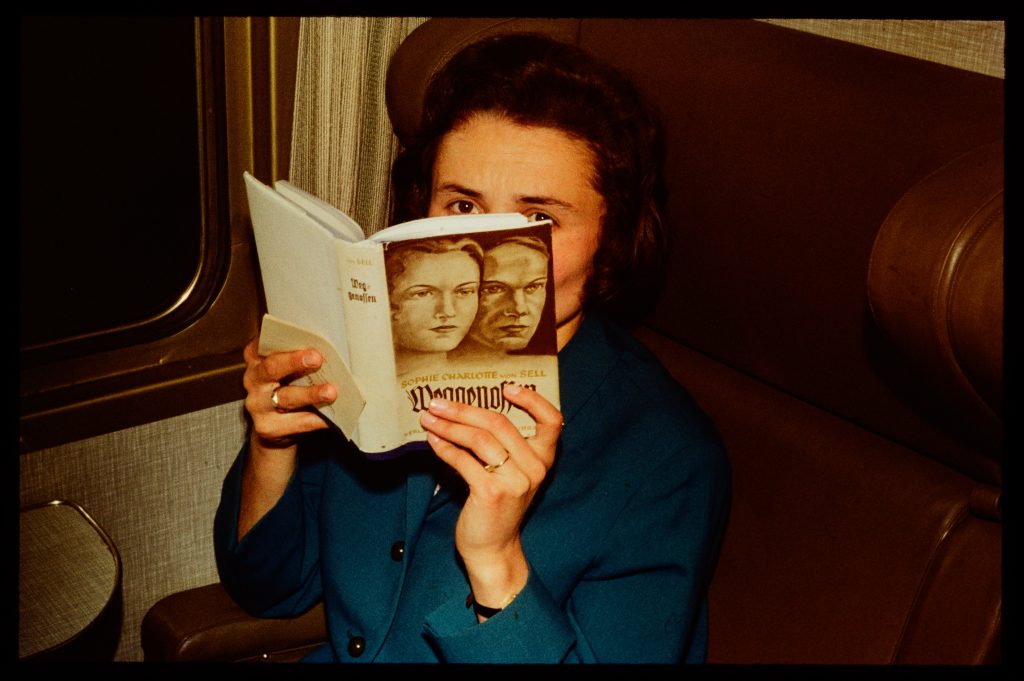

Many of the motifs seem unspectacular at first glance. A living room. A mountain landscape whose location I don’t know. People squinting in the sun. But that’s exactly what makes them valuable.

That’s how it really looked. That’s how my parents lived, laughed, and vacationed.

Some of the people in these pictures are no longer alive. Some places no longer exist as they originally did. And even where everything is still there, something crucial is missing: the moment. You can’t reconstruct it. You can only lose it.

Slide film forgives nothing. Colors slowly shift to red, contrast disappears, sometimes mold eats into the image. It happens quietly. And at some point, it’s too late.

Digitization is not a hobby here. It’s a rescue mission.

The scanner and a clear conscience

At first, the classic slide scanner feels right. Respectful. Careful. Each slide individually, every little detail checked. There is something calming, almost meditative about it.

Until you start doing the math.

Two, three, sometimes five minutes per slide. Preview, settings, final scan, dust correction. You sit there and watch the progress bar while a mountain of boxes shrinks imperceptibly.

With 10,000 slides, that means months. Evenings, weekends, vacations. And at some point, a thought creeps in that you don’t want to have:

Can I even do this?

The scanner makes beautiful files. But it eats up time. And time is exactly what these images lack.

The camera. And suddenly everything changes.

The idea of simply photographing slides felt wrong at first. Too fast. Too technical. Almost disrespectful to the material.

But then the setup is ready. Camera aligned. Light even. First test shot. And suddenly something unexpected happens: it’s working.

Insert. Click. Change.

No waiting. No calculations. No progress bar.

Three, four, five, even ten seconds per slide. The stack is visibly getting smaller. After an hour, you have saved hundreds of images. Not perfect. But saved.

And that changes everything. Overwhelm turns into control. Procrastination turns into feasibility.

Perfection can wait. Memories cannot.

Yes, the scanner is better in some ways. Automatic dust correction. Perfectly reproducible colors. But what good is perfect quality if you can only manage a fraction of the task?

The camera delivers RAW files with enormous scope. Colors can be corrected later. Dust can be retouched. But only if the image exists.

Looking at my parents’ photos, I realized:

- Better to have a picture than none at all.

- Better to have it complete than perfect.

In the end, you sit differently in front of these pictures

Once the digitization is complete, you look at the photos differently. No longer through the slide. No longer under time pressure. But in peace.

You recognize faces you had almost forgotten. Situations that were never talked about. You see your own parents younger, more carefree, sometimes tired, sometimes silly. And you realize that you have preserved something here that would otherwise have been lost.

It’s not about scanners or cameras.

It’s about these images remaining.

And not having to ask yourself later why you waited too long.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.